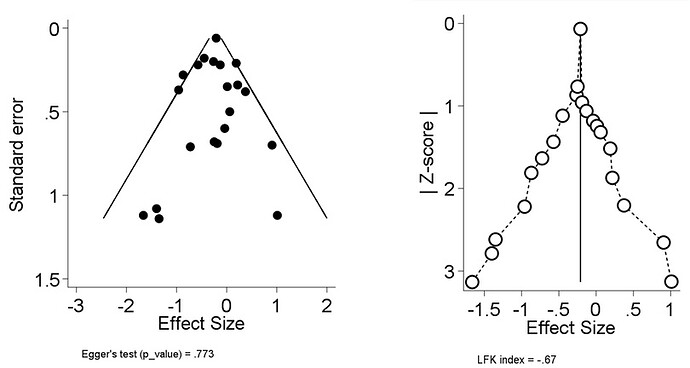

Thanks for the question @GJB. As you are aware funnel plots cannot be used with meta-analysis of prevalence for various reasons and so the Doi plot solves that. The interpretation is as follows:

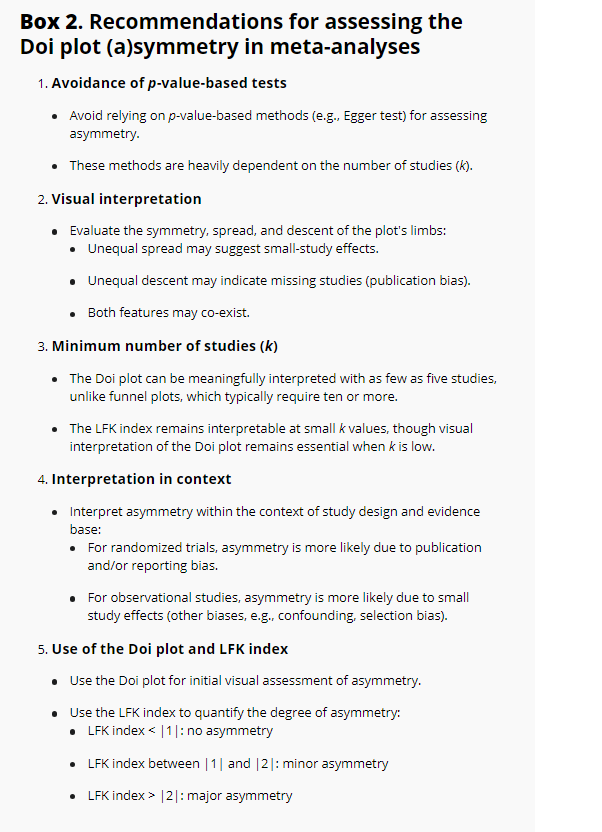

In addition we gave this recommendation:

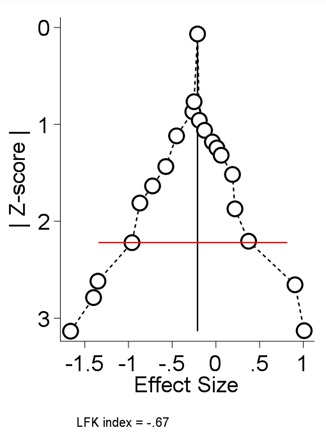

" The visual assessment of the Doi plot depends on the spread, descent, and number of studies on its two limbs. Three examples illustrate these concepts:

1. Small study effects: Both limbs have a similar number of studies and descend equally from the tip, but one limb is more spread out from the center line as study sizes decrease.

2. Publication bias: One limb has fewer studies and descends less from the tip, though its spread matches the other limb until its descent, indicating missing studies.

3. Combined effects: Both limbs descend equally, but one limb has fewer, more widely spread studies, indicating both small study effects and potential missing studies.

Thus, the visual assessment of Doi plot asymmetry remains critical when assessing asymmetry due to random or systematic error, as explained above (Box 2**, Recommendation 2***).*

The Doi plot has several other advantages, it can be used even with five studies, as corroborated by the simulation results in this study. Nevertheless, systematic review authors should carefully distinguish between potential causes of Doi plot asymmetry and consider factors such as the intervention, its context, and variations in study design when interpreting findings. Furthermore, unlike funnel plots, the Doi plot imposes no restrictions on outcome scales, making it applicable to a wide range of metrics, including prevalence and standardized mean differences (Box 2**, Recommendations 3 & 4***).*

While the Doi plot and LFK index are also applicable to meta-analyses of observational studies, effect estimates may become asymmetric due to decreases in quality (e.g., confounding and selection biases) of the primary studies. In such cases, asymmetry may reflect not just publication or reporting biases, but also differing degrees of other biases between smaller and larger studies (Box 2**, Recommendation 4). To address this issue, especially in observational studies, some researchers advocate stratification by quality (higher vs. lower based on an arbitrary threshold) or risk of bias judgments, but this should be avoided as this can actually create a scenario that creates spurious within stratum asymmetry. The use of quality or risk of bias assessments to bias-adjust meta-analyses may be a preferred approach."

Link to paper