Thank you Edward for your thoughtful input. You elegantly presented the standard argument for the PettyBone lumping paradigm of critical care which has been promulgated for many decades. It great for everyone to see exactly what that argument is. That would be a well received editorial for the journal Critical Care Medicine.

Yet, this is a statistics and data methods forum so we are going to be asking for more specificity then you provided. I hope you will stay and bring that specificity by correcting any perceived errors I have made in the analysis I provide below. You state:

Very well, I know critical care scientists think the term “heterogenous syndrome” is meaningful, but since this is a data methods forum, not a Critical Care Medicine or Blue Journal editorial, we don’t have the luxury of using ambiguous terms of art. For us to understand you, you have to objectively define what you mean by the standard critical care term “heterogenous syndrome”?

The adjective “heterogenous” is ambiguous and the noun “syndrome” is ambiguous. So the phrase “heterogenous syndrome” is, linguistically, the product of two ambiguous words, so in a sense it is “ambiguity squared”. This is not a flippant determination because it is exactly ambiguity squared that critical care scientist ask the statisticians to study using math to render reproducible results.

Here is the answer the to the question; What is a “heterogenous syndrome?”*?

My Answer: ***A heterogenous syndrome is a disease agnostic first mathematical SET of tens or hundreds of different diseases which fall within the scope of a second mathematical set of non-disease specific thresholds.

(This second set of thresholds can be determined as a best guess, either by one person or a consensus defining group, or otherwise the second set of thresholds can be defined by machine learning. This standard second threshold set for all to use worldwide in RCT is ONLY amendable by a select consensus group task force, but these amended set of thresholds need not overlap the prior threshold set . In other words the tasks force need not build on the past but can guess anew. )

So now that we have established that critical care scientists have been testing treatment for “heterogenous syndromes” the past 3 decades, we obviously have no idea what they have actually been testing treatment for. Worse, neither do they.

For this reason arguments relating to the testing of heterogenous syndromes are impossible to follow because it is not possible to study, with math, “ambiguity squared” and render actionable, reproducible outcomes. In fact given that, it is not surprising Edward that you say:

Indeed, under the PettyBone paradigm, RCT broadness is undefinable.

Of course the argument that the world is complex and the work is difficult is not a pass to continue PettyBone RCT. The brilliant Bradford Hill shows how to engage complexity by narrowing the method to test to a single phenotype of a single disease wherein the outcome is measurable.

That, at least some, of critical care science, are now narrowing the target is commendable, but the masses of critical care scientists and statisticians of the world have their marching orders for RCT lumping using SOFA and the ARDS threshold sets. That a few elites are finally recognizing that the PettyBone RCT is pathological science, while still letting the rest of the world flagellate using the standard research PettyBone lumping guidelines, without disclosure that this is pathological science, is not mitigating.

A critical care scientist might argue that the heterogenous syndrome is something that “we just know about”. A sociological construct of sorts. But the composition of each second threshold set which have been promulgated as a world standard to capture each first set of diseases of a heterogenous syndrome prove that not even this is true. SIRS (Bone’s original threshold set which lasted from 1989 to 2015 has no mathematical or biological similarity with either the signals or the thresholds of SOFA, which is presently promulgated as the world standard for research. Furthermore, the present standard ARDS thresholds sets have little similarity to the set guessed in Berlin in 2012 (which failed during the 2020 pandemic).

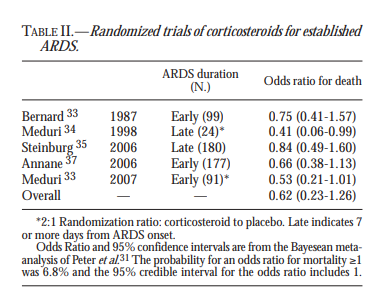

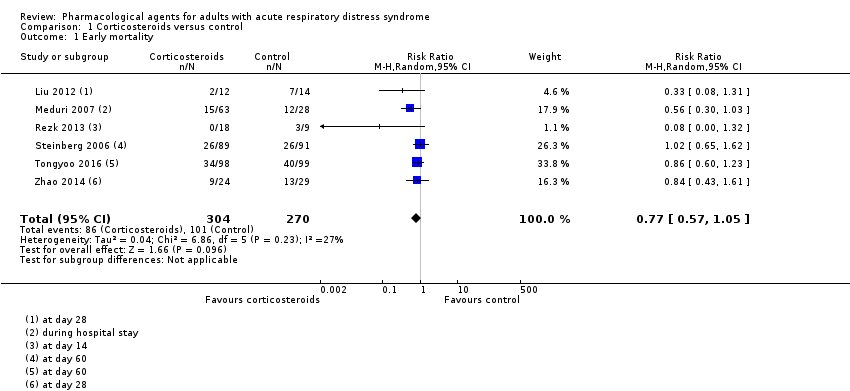

The argument that one can always slice bread thinner, while true, is not an argument for studying lumped ambiguity squared. Indeed, you make the argument that there is no dichotomy between the PettyBone RCT and the Bradford Hill RCT. I disagree. A sepsis RCT using SIRS or SOFA is so far on the PettyBone end of the spectrum as to be defined as completely opposing Bradford Hill’s teachings. It is the study of a heterogenous syndrome, in other words it is an RCT testing a treatment of ambiguity squared. But we don’t need to ask Fisher or Hill how well the PettyBone RCT works, we have over 3 decades of proven failure.

Certainly I do agree with you there is a spectrum once you move outside of using RCT to test treatments for heterogenous syndromes. The CAPE-COD trial is much more on the Bradford Hill side of the spectrum then the PettyBone sepsis and ARDS trials. Indeed, studying bacterial pneumonia is not diagnostically agnostic. However, as Erin points out, there is still a component of PettyBone lumping which should give any informed practitioner considerable pause at the bedside.

When I started this campaign against lumping in social media in 2012, the “thought leaders” were so far down inside the dogma that they were aggressively defending Bone’s guess of SIRS. They were not even close to understanding that they were doing PettyBone RCT testing treatments of ambiguity squared. With terms of art like “heterogenous syndromes” they fooled themselves and indoctrinated the young. We all did this in the past.

That your team and others of critical care science have now come around to see the folly of the PettyBone dogma is indeed progress, but the editorials and discussion should be very much more forthcoming, admitting the past mistake and teaching the truth to the statisticians who they fooled into thinking that a given heterogenous syndrome was a well thought out “disease equivalent” for a Bradford Hill RCT.

I did not stumble upon this problem as you imply, I did a comprehensive root cause analysis of the failure by exploring the history of critical care science and its dogma to understand its failures. Root cause failure analysis of fundamental dogma (such as the PettyBoneRCT methodology) is not something the young critical care scientists are taught. Also, I was not the first to provide warning. Murray. a master pulmonologist, argued, in an editorial, that Petty’s lumping idea was not sound in 1975.

It is true that some in critical care are now aware they have a problem but they do not examine it in the open by a root cause analysis process. If they did they all would see we have been been practicing pathological science by pathological consensus.

Over a decade ago I once believed the dogma and taught these things. Although I never taught SIRS (Bone was my contemporary), and of course not SOFA as lumping tools for RCT, still, at first, I thought Bone’s methylprednisolone trial was a good idea and meaningful. We were all indoctrinated but now we have to tell the entire truth so that does not happen to the next set of mentees. We have to save the public. The political considerations of critical care science are irrelevant.

To the point of identification of what we need to change, I have found that the standard terms of art, which critical care science thinks are valid, are so ambiguous that any discussion at the level of the mathematical function of the RCT itself is never possible. The discussion and debate and pro con sessions while appearing real remains superficial. I have a term for this. This is “synthetic debate” about “synthetic syndromes”. The statisticians and indeed the debaters themselves are fooled into thinking a heterogenous syndrome is an objective biological entity.

Root cause analysis is not possible as long as “ambiguity squared” is still a valid term of art.

Thank you Edward for your excellent contributions to to this discussion/debate. I hope you will stay and continue the dialog. I hope you will send your colleagues. This PettyBone RCT thread has had over 3000 readers so a complete discussion on all sides is important. We also look forward to their comments.