As promised, I will describe the changes which need to be made.

[quote=“ESMD, post:57, topic:22077”]

Let’s pretend that some brave statistician (or group of statisticians) were to publish, tomorrow, a long article about how wrong all your clinical colleagues have been for so many years

[/quote] (emphasis added)

First you may not know it but very many of my colleagues agree with me not the “task force, triage threshold sets for RCT, generators”. As you know it’s not expedient to speak up.

So perhaps this was your intent and, if it was, “hats off”, because your quote beautifully betrays the gravest fundamental problem. This problem is that in the present culture of critical care science, it takes bravery to publish an anti-dogmatic article. In contrast, in Wood’s time, as lauded by Langmuir, this was a badge of honor. Science policing was the responsibility of all. Now, with the new consensus and task force class culture, it risks the career.

So, pretending, as you propose, that the social paternalistic/maternalistic bubble of the central control of the task force class can be pierced, here are the steps which need to be taken.

- The first step the NIH should take is to empower with funds, the statisticians to lead by funding them independently from the PI. They would be co authors and responsible for the methodology. They would be selected by a process which does not include the PI. If the statistician is responsible for the entire function including the basis for the measurements then, of course, she would investigate the terms of art like “heterogeneous syndrome” and convert them into math. That would change the paradigm very quickly. The apical error would be eliminated.

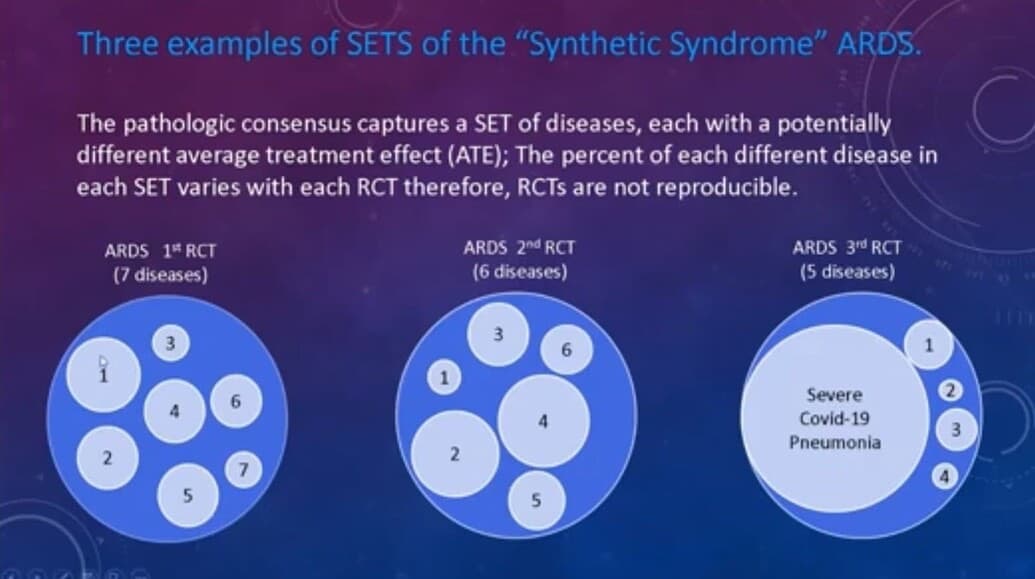

As Prof Harrell points out a pivotal part of the mathematical function of the RCT is the presence of a “homogeneous thread”. The lack of this thread is the apical error but this error has been unrecognized by the principal investigators and this created the present PettyBone era.

So empowered, the statisticians would stop assuming the PIs have sufficiently investigated the basis for the lumping. They would then assure, with the PI, that this common thread is present.

Here you see the difference between a PettyBoneRCT and a Bradford Hill RCT is the presence of a homogeneous thread in the latter.

The traditional means to assure a homogeneous thread was well described by Hill. However science has advanced so a homogeneous thread may be a measurable fundamental pathology common to all in the subjects by many means. It may even be a hypothetical common thread as it was with Petty and Surfactant if there is a solid discovery basis for that hypothesis. However we now have learned to our sorrow that one cannot simply lump by guessing, as Petty, Bone and decades of triage threshold generating task forces have, lest the thread be lost in the disease mix.

- The second step the NIH should take is to summarily defund the non disease specific threshold set consensus generating task forces. This is the 33 year source of pathological consensus and a major cause decades of critical care PettyBone RCT failure. The attempt to unify the world’s RCT funding by guessing triage threshold set “criteria” for the RCT is the dripping open wound of 33 years PettyBone pathology. Source control is required when curing any pathology and these task force, Delphi (guessing) triage threshold set consensus meetings, which recur every decade, are the source. The funds should be redirected to meetings of experts seeking to discover common threads.

PettyBone guessing leaders (who guess non-specific threshold based lumping science) meeting should be replaced by meetings of bench and clinical discovery scientists and expert statisticians.

- Since we are pretending that the reasons for the failed PettyBone paradigm

has been promulgated by amazingly altruistic and “brave statisticians” then the third step of releasing the thousand points of youthful genius light to advance critical care will already have occurred in this idealized, altruistic paradigm.

Upon this promulgation, the search for the homogeneous threads at the bench and in the databases and at the bedside will be empowered and these searched will not have to link their discovered thread to the consensus guesses of the task force class. Some of this is emerging with the “treatable traits” approach but the world’s scientists must be released to search for such threads without regard to the edicts of the task force. Because of past paternalistic indoctrination AND intellectual colonization with the PettyBone error USA critical care science owes this cathartic promulgation to the rest of the world without delay. Because this release only happens if the trusting and intellectually colonized critical care scientists in the rest of the world are, without delay, told the whole truth.

So Erin the fix is easy because the apical mistake of the pathological science is the straightforward loss of focus on the need for a fundamental homogeneous thread.

So where should this discussion go once the PettyBone apical error has been eliminated?

Once the critical care research community at large is released from the well intentioned, central control of the paternalistic heterogeneous syndrome apologists and control is transferred to the entire community as individuals and as a whole and debates turn to;

“What constitutes a homogeneous thread?”,

rather than;

“What is the new consensus task force derived threshold set to triage for RCT?”

When that happens, and it will, because this reform can only be delayed not stopped, there will be no more need for my antidogmatic efforts.

I hope you will come back Erin. I have so much enjoyed and respect your thoughtful comments and I think they are very helpful for the silent readers.

Zeal in the quest for science is no vice.