Dear all,

I contacted @f2harrell by email regarding a protocol for a survey I am planning as part of my PhD (my background is physiotherapy). Frank suggested moving the discussion to the forum. This post is detailed because I think the method is not widely known. Thank you for bearing with me.

Background

An issue that interests me is how we determine whether between group differences observed in RCTs are meaningful from a patient perspective.

Most often, the minimally important difference (MID) concept is used 1, 2. However, methods typically used to derive MIDs have been criticised (this paper describes the issues well).

Currently, the dominant method involves anchor-based approaches 3.

- E.g, one determines the mean change from baseline in a PROM (e.g., a pain scale) among patients who rate themselves as “somewhat better” on an external anchor (e.g., a global rating of change scale, GROC).

- In this case, the MID is actually derived from within-group changes and represents a minimally important change (MIC) 4.

- Despite this, these estimates are widely used to interpret between-group differences in RCTs, meta-analyses and guidelines 5, 6.

- This is conceptually flawed 7

In addition, distribution-based methods (e.g., defining the MID as 0.2 SD) or other arbitrary thresholds are sometimes used – but these approaches a) arbitrary and b) completely ignore the patient perspective.

Finally, none of these methods explicitly account for the risks, costs, or inconveniences associated with interventions. Often the same MID is applied to interpret between group differences of very different comparisons. But logically the MID for an comparison where one intervention carries risk of significant harms (e.g., surgery vs non-surgical treatment) should be higher than that of a comparison without such harms (e.g., education vs no treatment).

The smallest worthwhile effect

To overcome these issues, Barrett et al. introduced the smallest worthwhile effect (SWE) 8:

“The smallest beneficial effect of an intervention that justifies its costs, harms, and inconveniences.”

Key features of the SWE according to Ferreira 2018:

- Must involve healthcare consumers.

- Must be intervention-specific, considering the treatment’s harms, costs, and inconveniences of two options.

- Must be defined in terms of the contrast between intervention and control, not just change over time.

The benefit-harm trade-off (BHTO) method can be used to elicit the SWE:

- Risk, costs and other inconveniences of two treatment options are explained.

- Expected outcome with control option is presented (e.g., non-surgical treatment).

- Patients are asked what additional benefit they would need from the intervention option (e.g., surgery) to consider it worthwhile.

An example: SWE for NSAIDs vs no treatment

After presenting the relevant information about both options Hansford et al used the following script. Other studies have used a similar structure.

“If you didn’t take the drugs your back pain could get about 20% better in the next week as this is the natural course of low back pain.

However, if you were given the anti-inflammatory drugs, how much additional reduction of your pain would you need to see to make the drugs worthwhile?”

Participants entered an additional improvement between 0 and 80% (e.g., 40%). This value was then reduced:

“Now, suppose you only got 30% better on top of the initial 20% improvement (ie, a 50% total reduction). Would that be enough of a reduction in pain to make the drugs worth their cost and side-effects?”

(Iteratively decreasing the benefit until the patient says “No.”)

The smallest additional improvement the patient accepts is their SWE. This is repeated for each patient. At the group level the SWE is usually reported as the median.

In this case the median SWE was 30% (IQR 10–50%). This is interpreted as 50% of participants would consider taking NSAIDs worthwhile if it improved their back pain by an additional 30% compared to no treatment. One could also use the 80th percentile (effect considered large enough to be worthwhile by 80% of participants) 9.

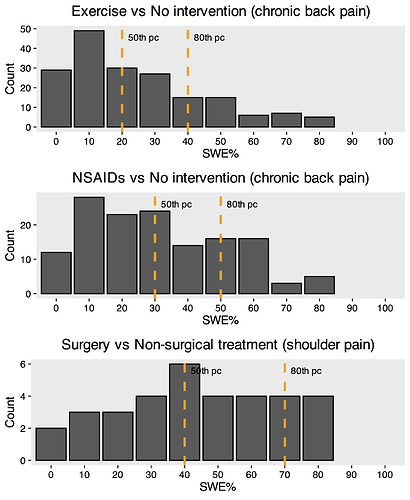

Below you see bar graphs of SWE values from that study and another one by Hansford. In all scenarios a 20% improvement with control was presented.

Summary: The SWE was higher for riskier interventions (e.g., surgery vs exercise) underlining the point made in the background section.

How the SWE is applied to trial data

So far, researchers assumed the SWE is transportable because it is derived from %improvement of baseline:

- To apply it to trial or meta-analytic result you multiply the trial or pooled baseline score by the SWE %.

- You then compare the between-group difference to this threshold.

Example:

- Baseline back pain in a RCT = 6/10.

- SWE = 30%.

- 6 × 30% = 1.8 points.

Thus, a between-group difference ≥ 1.8 points would meet the SWE threshold for 50% of patients.

Is this valid?

My project

As part of my PhD I am looking at people with sciatica caused by a lumbar disc herniation with an indication for elective surgery. I aim to use the BHTO method described above to estimate the SWE for surgery vs non-surgical treatment on:

- Leg pain

- Back pain

- Disability

- Time to recovery

Specific questions and challenges

Framing of the survey (most important for me right now)

- How should I frame the BHTO scenario to ensure it is a) aligned with how patients think/ easy to understand and b) scientifically valid?

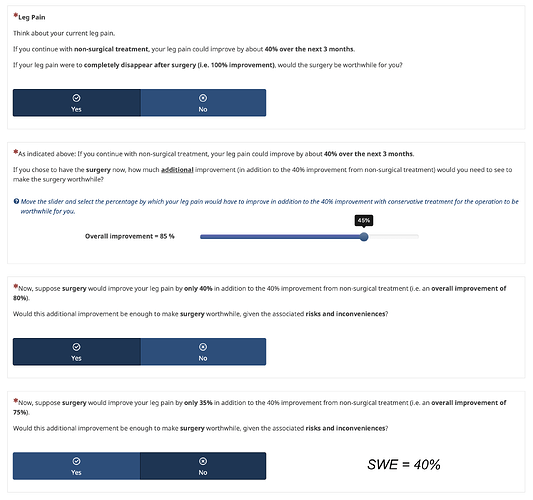

Initially, I framed SWE questions using % additional improvement, as in previous SWE studies (see an excerpt below).

Framing using %improvement:

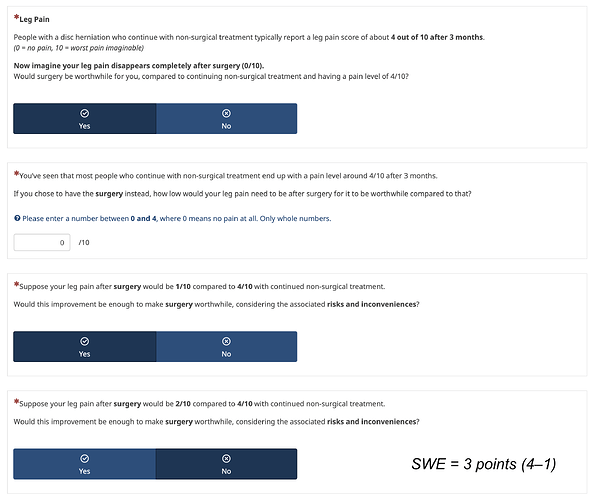

However, Frank noted in his email and here that “patients care most about their current status and little about how they got there.”

Thus, I am now exploring framing using the absolute score at 3 months.

Framing using fixed final score:

There are however various options on how to arrive at the final score. To inform the expected improvement with non-surgical treatment I pooled data from conservative arms of RCTs and cohorts of people with an indication for elective surgery. I can pool a) the follow-up scores, b) the change from baseline or c) the proportional improvement (see Table below).

| Outcome | Final score | Change from baseline | %Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leg pain (0-10) | 3.6 | -2.6 | 0.42 |

| Back pain (0-10) | 2.8 | -1.7 | 0.35 |

| Disability (0-100 ODI) | 30.6 | -15.1 | 0.33 |

I collect the patients current pain and disability which means I could “personalise” the expected outcome for each patient. But I am not sure if that is valid.

| Data | Calculation | Assumption about improvement | Example baseline leg pain (0–10) | Non-surgical outcome in survey |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed score | Pooled value at 3 months | ? | 8 6 |

3.6 3.6 |

| Change score | Baseline – pooled mean change | Additive change | 8 6 |

5.4 3.4 |

| % Change | Baseline – (Baseline × 42%) | Proportional change | 8 6 |

4.6 3.5 |

Which option should I choose? An issue with using the fixed final score could be if a participants baseline pain is already below that. I could set a certain pain threshold as an inclusion criterion.

For the other options I am not sure what is more valid an additive or a proportional change?

Also, if each participant’s expected non-surgical outcome is personalized, would this pose an issue for interpreting the final SWE estimates - since each participant would be making their trade-off relative to a different value? Could I/ should I adjust for the expected improvement with non-surgical treatment in a regression model?**

- Any advice on how to frame disability outcomes using absolute scores?

While I think patients can conceptualise a target like “4/10 leg pain”, this becomes much harder for something like “30/100 disability” on the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI).

This issue seems less pronounced when using percent improvement (although it is still difficult IMO) as in a previous study on SWE for NSAIDs. But there we have the issue of not having the final scores again.

“Now think about the daily activities that you can’t do as a result of your back pain. If you didn’t take the pills your ability to perform your daily activities could get about 20% better in the next week. However, if you were given the anti-inflammatory pills, how much additional reduction of your disability would you expect to see?” Ferreira 2013

- Median time to recovery or restricted mean survival time (RMST)?

For the outcome time to recovery I have estimates for both median time to recovery (12 weeks) and RMST (20 weeks) for the non-surgical treatment strategy. I want to know how much faster people would need to recover to consider surgery worthwhile. I thought to use RMST because I have never seen the difference in median survival times reported with a confidence interval. Any arguments for using one over the other?

Analysis

- Can I transform the absolute SWE to a proportional SWE to make it transportable across baseline score and scales?

The handy thing with using %SWE is that it can be applied to trials with different baseline pain for example (see above). Or if I have the %SWE for disability I could apply it to different scales that measure disability. When I use the final state framing I would get absolute SWE estimates, e.g. lets say the results of my survey would be that patients require an additional 3 point change in leg pain on a 0-10 scale to consider surgery worthwhile over non-surgical treatment. Could I transform that to an %SWE by dividing the individual absolute SWE values by the respective patients baseline and then take the median of that?

-

Any advice on sample size calculation to get a precise median estimate of the SWE? I used presize which works for means. Is there such a procedure for medians?

-

I want to explore whether patient characteristics influence the magnitude of SWE. Should I use ordinal regression? (see bar plots above for typical data structure)

-

If so how should I calculate sample size for ordinal regression with ~11 candidate predictors (12 DF, even more with splines)?

Other

- Do you see any other major methodological or framing problems?

Thanks for reading this long post!

I would greatly appreciate any advice, suggestions, or critiques.

@vigotsky I really liked this paper of yours. I thought this could be relevant about the underlying assumptions of improvement with non-surgical care. Would love to hear your thoughts too.

@VickersBiostats I think the method could overcome what you critiqued here and get us better comparison specific MCIDs. What do you think?

Best,

Florian