I’m not sure about this statement…

Most physicians were not trained to interpret regression equations (me included). So most of us have to trust that many eminently qualified statisticians were involved in the development of risk calculators that have been used globally for decades, and in advising physicians about how best to “transport” the results of RCTs to the patients we see in clinic. While not impossible, it seems, to me at least, quite implausible that we’ve all been doing things wrong for the past 25 years.

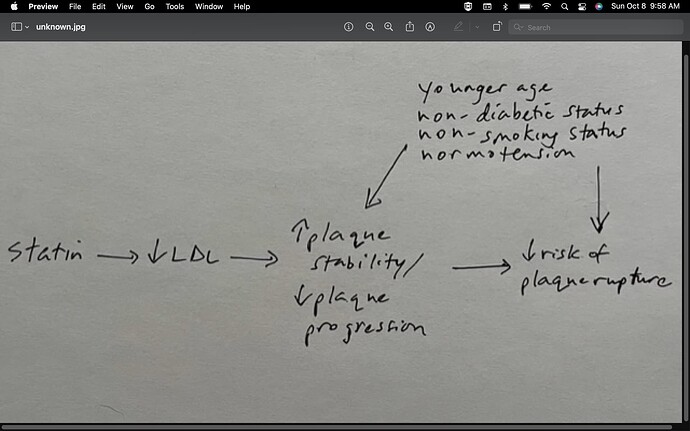

For whatever it’s worth, this is how I conceptualize the causal path:

I’m thinking of all this using the framework shown in figure 10 of this publication:

I’m thinking of all this using the framework shown in figure 10 of this publication:

I’m really trying to understand your concerns, Huw, and I wonder if the underlying causal diagram is the main point of contention. I sense that you perceive an inconsistency between how CV risk factors are treated in the process of estimating an individual patient’s future MI risk, versus how we conceptualize the potential “relative treatment effect” of statins.

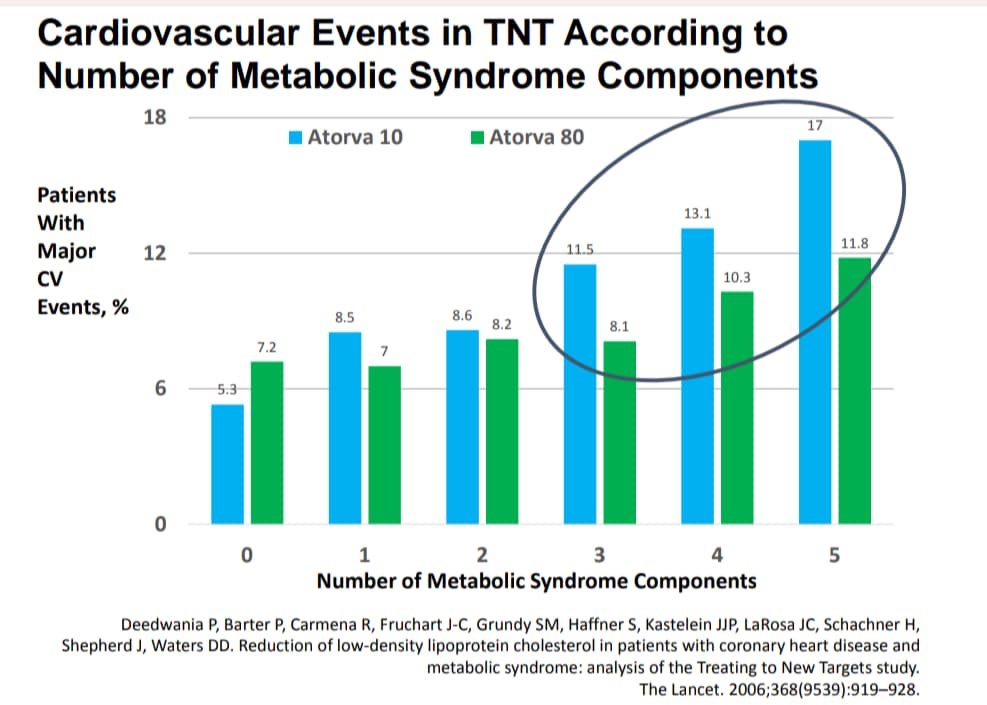

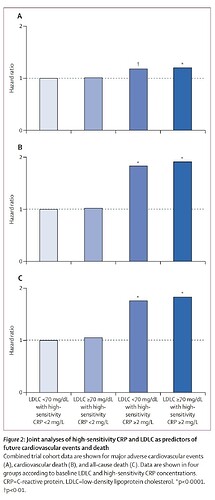

Specifically, you seem to be viewing CV risk factors as “prognostic” factors, such that non-lipid risk factors (e.g., smoking/HTN/DM2/age) would not be expected to biologically “modify” the relative treatment effect of statins (e.g., the HR) in a statin RCT. In contrast, my conceptualization above treats the non-lipid risk factors as both “prognostic” and “predictive” [a view that seems, to me, to be more in keeping with our current biologic understanding of the interactivity of various CV risk factors].

I sense that you are troubled by what you perceive to be a “bait-and-switch” with regard to how the medical community estimates potential statin benefits. I think you’re saying that if we are going to treat non-lipid risk factors as strictly “prognostic” for the purpose of estimating a patient’s future MI risk (i.e, no arrow from the other CV risk factors toward "  plaque stability/

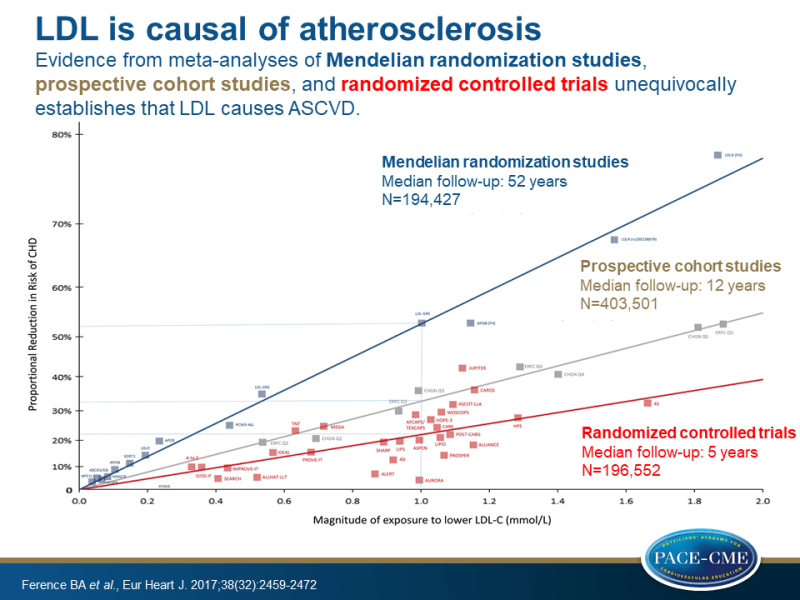

plaque stability/  plaque progression"), then we shouldn’t act like treating a patient with a “good” LDL with a statin could, under any circumstances, be expected to confer much CV protection (?) In contrast, as discussed previously, I tend to view the underlying known biology as strongly supportive of a view of LDL as interactive with the other risk factors, as though some patients will just “tolerate” a given LDL level better than others, depending on the presence/absence of other risk factors. While you seem to view the proposed interactivity of CV risk factors as post-hoc rationalization that is being used to bolster the perceived benefits of statins in primary prevention contexts, I view the interactivity as strongly supported biologically.

plaque progression"), then we shouldn’t act like treating a patient with a “good” LDL with a statin could, under any circumstances, be expected to confer much CV protection (?) In contrast, as discussed previously, I tend to view the underlying known biology as strongly supportive of a view of LDL as interactive with the other risk factors, as though some patients will just “tolerate” a given LDL level better than others, depending on the presence/absence of other risk factors. While you seem to view the proposed interactivity of CV risk factors as post-hoc rationalization that is being used to bolster the perceived benefits of statins in primary prevention contexts, I view the interactivity as strongly supported biologically.