Well my understanding is that there are two types of prior. The first is the so-called ‘unconditional prior’ that is actually conditional on a universal set, the latter being essential when applying Bayes rule.. A Bayesian prior is conditional also on prior knowledge of the study or other additional information such as the SNR. My understanding is that Kass (1990) is addressing other such ‘conditional prior’ information.

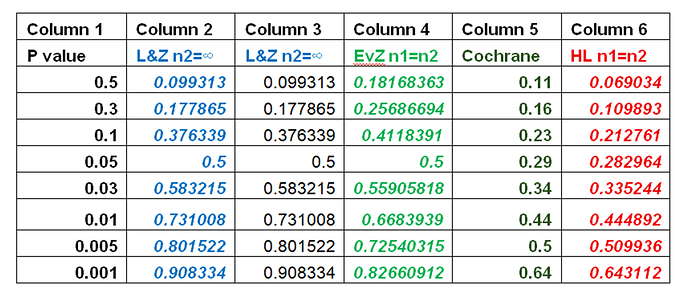

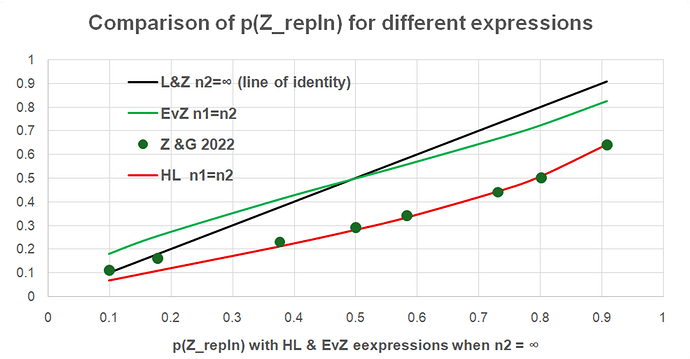

Now it sees to me a matter of judgement as to how or when to incorporate such other prior knowledge and their ‘conditional prior’ probabilities into a calculation. In my case I only assume a flat prior and Gaussian distributions but no other ‘conditional prior’ in my expression, the calculations being conditional only on b, s, n1 and n2.

P(Z_{\text{repln}} > 1.96 \mid b, s, n_1, n_2) = \Phi\left( \frac{b}{\sqrt{\left( \frac{s}{\sqrt{n_1}} \right)^2 + \left( \frac{s}{\sqrt{n_2}} \right)^2}} - 1.96 \right)

It is also my understanding that there are no right or wrong opinions, but only those that have been justified logically based on clear facts and assumptions and those that have not.