Presently there is a disturbing and growing outcry in social media that physicians willfully placed patients with COVID pneumonia on invasive mechanical ventilators, negligently contributing to their death. This misguided narrative is hard to understand and, of course, completely false.

However, where did this bizarre idea come from? It appears that a plurality of social media influencers have advanced this retrospectively derived narrative, citing the approach, early in the pandemic, to proceed with early mechanical ventilation, which was later changed.

Of course, the narrative is absurd because, whenever possible, protocols and physicians actions are based on the evidence. However what if that evidence is unknowingly wrong? What if the consensus is unknowingly wrong? This is the danger of consensus. If it is wrong this magnifies the error, potentially worldwide but provides a false sense of security to stay the course despite failure.

Recall that Langmuir in 1953 described “Pathological Science” as derived from an early unrecognized error (upstream) in measurement unknowing causing false laboratory results. In contrast “Pathological Consensus” is where the error in measurement of Pathological Science is expanded by promulgation (and mandated for research), potentially worldwide, by consensus, so the false results are generated and applied worldwide, not just in the laboratory. So the greatest risk associated with a trial is that flawed results will be considered actionable leading to adverse outcomes on a worldwide scale. This is exactly what Pathological Consensus can cause.

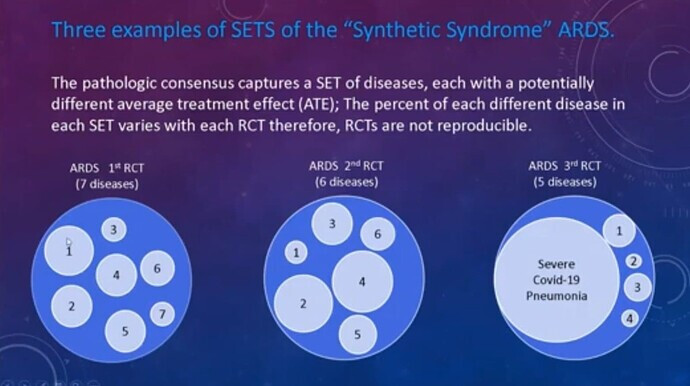

Recall Pathological Consensus is the strange 20th century “science” (which is still the standard in critical care today) where guessed consensus sets of thresholds replace discovery and are the gold standard measurement for RCT (until the set of thresholds is changed every decade or so). .It is a domain in which critical care syndrome science operates and where variable SETS of different diseases with disparate average treatment effects are captured by these guessed sets of thresholds (i,e, measurements or criteria) causing non reproducibility of the RCT…

However, how does this relate to the issue at hand, specifically, early invasive mechanical ventilation in COVID pneumonia?

Consider this seemingly robust 3 year study (albeit observational) from 2016 which concluded a significant increased rate of failure occurred when patients with “ARDS” (and low P/F ratio), were initially treated with non-invasive ventilation (NIV) rather that invasive mechanical ventilation.(IMV). When COVID pneumonia emerged in 2020 and met the broad 2012 Berlin consensus measurements for “ARDS” this article provided a perceived “evidence basis” to proceed with early invasive mechanical ventilation This was later abandoned due to high death rates.

Now let us examine this trial. First we can’t fault the authors or the physicians who trusted the trial, because It has all the hallmarks of standard ubiquitous and indeed mandated critical care research to use measurements derived from “Pathological Consensus”: Remember the hallmark of Pathological Consensus is the use of guessed threshold sets as measurements for RCT and other trials. See link: What is a fake measurement tool and how are they used in RCT

When we examine the methods and conclusion of this trial we see all the standard characteristics of 20th century “Syndrome Science”.

- The measurements are a guessed set of thresholds from 2012 (the Berlin Criteria)

- A WIDE range of different diseases are captured by the consensus measurements

- The captured diseases causing the “ARDS” were pulmonary in 58.8% & extrapulmonary in 32.9%

- The syndrome (ARDS) is a cognitive bucket guessed in 1967 comprised of many disease with diverse pathophysiology including viral pneumonia.

- The authors generalize their conclusions to “ARDS”, and therefore generalized the results to, all the diseases captured by the measurements of ARDS as is standard with “Syndrome Science”.

The authors conclude that a high rate of NIV failure occurred in patients with a “low baseline Pao2/Fio2 ratio” and “ARDS” so invasive mechanical ventilation will likely be required.

When the COVID pandemic developed (many having a low P/F ratio) this provided standard Syndrome Science level “evidence” to proceed with early intubation and invasive mechanical ventilation which has now appeared to be a less than optimal approach in at least a portion of the cases. This is the action taken up by the self serving social media provocateurs in their ill-conceived, follower deriving, rants against physicians.

However, here again we see the danger of using measurements for trials (RCT or otherwise) which first capture a range of diseases and, second, generalizes those results to any single disease (and all diseases) captured, especially a disease that was not included in the trial and worse, did not even exist at the time of the trial. However this is the hallmark of Syndrome Science, the standard science of critical care today…

How could that happen? How could invasive early mechanical ventilation be considered “evidence based” if no patient who actually had the disease under care was in the trial? Under 20th century “Syndrome Science” generalization of the results to diseases that were not in the trial is actually considered correct.

The fundamental axiom of the present critical care research standard (20th century “Syndrome Science”) is that the disease does not matter. The conclusions of a study applied to a guessed “syndrome” are applicable to all diseases which meet the guessed threshold set measurements of the syndrome. Indeed, the results of the trial even apply to those diseases which were not included in the trial but meet the measurements of that syndrome, and that includes a disease which did not exist at the time of the trial but retrospectively meets the measurements of that syndrome.

This is why the results of a trial of “ARDS” were generalized to a disease (COVID Pneumonia) which did not even exist a the time the measurements for ARDS were guessed (or the trial itself was performed). This last feature (applying conclusions to a disease which did not exist) is how one absolutely knows that Syndrome Science IS NOT valid science and must be soon discarded.

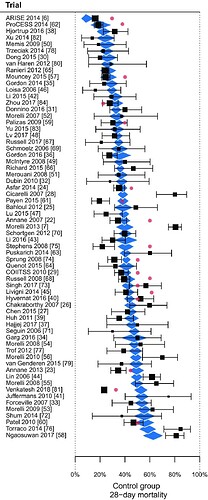

Remember this graph from the previous post. The End of the "Syndrome" in Critical Care

However, non-reproducibility of the results is not the primary risk. The primary risk is that the results will be considered actionable for all diseases which meet the guessed threshold set of measurements. This is what happened in the spring of 2020.

Its easy to see this in retrospect now but at the time, early in the pandemic, no good physician was going to sit by while the patients appeared that they would certainly die of this novel disease without ventilator support. Also, as indicated, there were other very valid reasons why physicians felt that early intubation and invasive mechanical ventilation was indicated. This of course was considered by virtually all considering the extant evidence to be the best care and was delivered by caring physicians risking their lives.

In critical care, all a physician can do is diligently strive to apply the best care, whether that turns out to be the optimal care can only be defined by the passing of time, sometimes the required time is measured in years or decades.

Even so, 40+ years of Syndrome Science of ARDS has proven to be a failure. Just say No to Pathological Consensus.

References:

**Origin of “Syndrome Science” **

1975 Tom Petty describes his new guessed syndrome (ARDS) as including viral pneumonia:

Rebuttal of Tom Petty’s guess in 1975 (we should have listed to this)

45 years later in 2020, conflation of Tom Petty’s guess (ARDS) and severe COVID (viral) pneumonia

A post pandemic “plea for honesty” as it relates to “Syndrome Science”

Global consequences of 40+ yrs of “Syndrome Science” & “Pathologic Consensus” on world health.

Discussion of “ARDS” as a “Sociological Construct” for trialists. All statisticians should understand this is the essence of “Pathological Consensus”. Fake measurements render useless statistics. Just say NO!