It would be nice if you found our discussion illuminating, but I think you’re just being sarcastic. I certainly had a very poor experience trying to discuss your preprint with you.

In a statistics paper, we try to be very clear about the model and the statements we derive from it. In particular, we try to be very clear about how all the variables are defined.

Your preprint is quite different from a statistics paper. It has some figures, some numbers and a lot of talk (“all possible observed means of a continuous variable are conditional on the universal set of all numbers” and things like that). There are no clearly defined variables, there is no clearly defined model and there are no clearly derived statements.

Of course, the fact that your preprint doesn’t look like a statistics paper does not mean there’s anything wrong with it! So I wanted to be helpful by introducing proper notation to clarify your model and your conclusions. This turned out to be extremely difficult. Finally, in post 215 (!) we managed to agree on

Model: We are assuming the uniform distribution on \beta and

b \mid \beta,v_1 \sim N(\beta,v_1) \quad \text{and}\quad b_\text{repl} \mid \beta,v_2 \sim N(\beta,v_2).

Moreover, b and b_\text{repl} are conditionally independent given \beta.

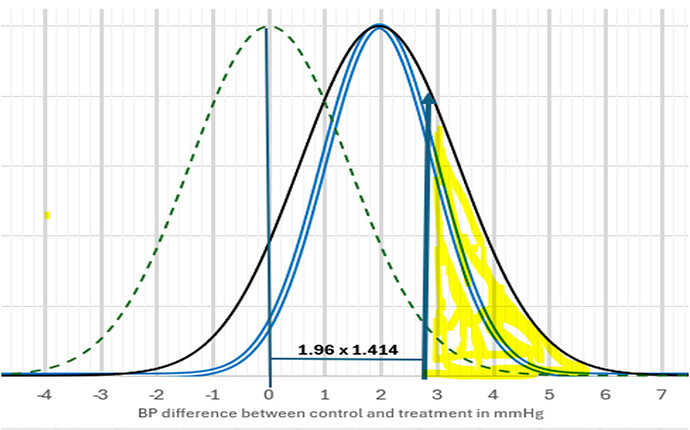

Now that we have a well-specified model, we can do math. If we define z_\text{repl} = b_\text{repl}/\sqrt{v_2}, then we have the (provably) correct statement

P(z_\text{repl} > 1.96 \mid b,v_1,v_2) = \Phi\left( \frac{b - 1.96\sqrt{v_2}}{\sqrt{v_1+v_2}} \right)

and the (provably) false statement

P(z_\text{repl} > 1.96 \mid b,v_1,v_2) = \Phi\left( \frac{b}{\sqrt{v_1+v_2}} - 1.96\right).

I was amazed that you continued to argue in favor of the false statement. That’s just crazy! The issue was finally resolved by introducing a new variable, namely z^\text{Huw}_\text{repl} =b_\text{repl} /{\sqrt{v_1+v_2}}. Now we have the true statement

P(z^\text{Huw}_\text{repl} > 1.96 \mid b,v_1,v_2) = \Phi\left( \frac{b}{\sqrt{v_1+v_2}} - 1.96\right).

I was again amazed that you claimed I misrepresented your views when I had derived your own “predictive replication probability” in the context of the model we had agreed on! Maybe you didn’t like the name z^\text{Huw}_\text{repl}. Perhaps I should have used x_\text{repl}=b_\text{repl} /{\sqrt{v_1+v_2}}. A rose by any other name …

Now that we have some true statements, we can discuss the merits of your contribution. Assuming the uniform prior on \beta, you compute the predictive probability of the event |z^\text{Huw}_\text{repl}| > 1.96. I do not think this is useful for two reasons

- The uniform prior on \beta is unrealistic.

- The event |z^\text{Huw}_\text{repl}| > 1.96 is uninteresting because “replication success” is commonly defined as |z_\text{repl}| > 1.96.

In closing: The main problem I’ve had trying to communicate with you about math and statistics, is that you seem to think in terms of “my” and “your” statements. However, in a correctly specified model there are only true and false statements, and we can use math to sort out which is which. Once we have a true statement, we can discuss its merit or usefulness.